Public Data Cultures out today in UK! 🎊📦📗✨

October 23, 2025

My Public Data Cultures book is out in the UK today! 📗🎊

Several copies of the book arrived carefully packaged in a big brown box, which brought back memories of how my sister and I loved playing with empty boxes when we were kids. 📦✨

It is surreal to see the book out in the world - and finally having a life of its own. It is no longer living on my laptop! 😲

I’m writing this with a couple of copies in a shanzai Totoro bag my auntie gave me, on a train towards teaching a class on web archives and then joining for the (serendipitously timed!) launch of a new data empowerment clinic.

The book began with a conversation on a boat in Amsterdam 15 years ago, in which Liliana Bounegru asked about connections between my work with data by day and graduate studies in philosophy and critical theory by night.

That seeded the idea of writing something on the cultures and politics of public data.

The book grew layers through spending time with friends and colleagues studying new media and data activism in Amsterdam and then with a group in Paris set up by the late Bruno Latour as he was working on some of his last books and exhibitions.

My dad had a debilitating stroke in 2016. I started a fellowship to be closer to him in hospital and then at home. It felt like the world changed in many ways that year. Perhaps to feel less far apart, a group of us set up a space for socially engaged research across our places.

I continued working on the book when starting to work in London in 2017 going back and forth between classrooms, hospitals and home visits. My dad died in 2019. We put a bench under a giant sequoia in his memory.

I thought this would feel like someone leaving a room, but it was more like the whole room changed. I became an uncle later that year. Seeing my sister with her baby made me think about how the world together is put together piece by piece.

And then the pandemic, and all the changes that those years brought, and did not bring. As well as their brutality and bleakness, it felt like there were also glimpses of re-gathering, solidarity and hopefulness amidst unfolding polycrises.

Spending time with data investigations, poetic computation, live coding and community organising opened up space for reflective practice, inventive formats and using more of the available range.

Over the course of these years the book grew, evolved and changed shape as the world did and as we all did. It grew to a somewhat feral hundred and fifty thousand words, before being pruned to a more pocketable fifty. Its focus shifted from critical retrospective (though there is that) to feeding re-imagination and recomposition.

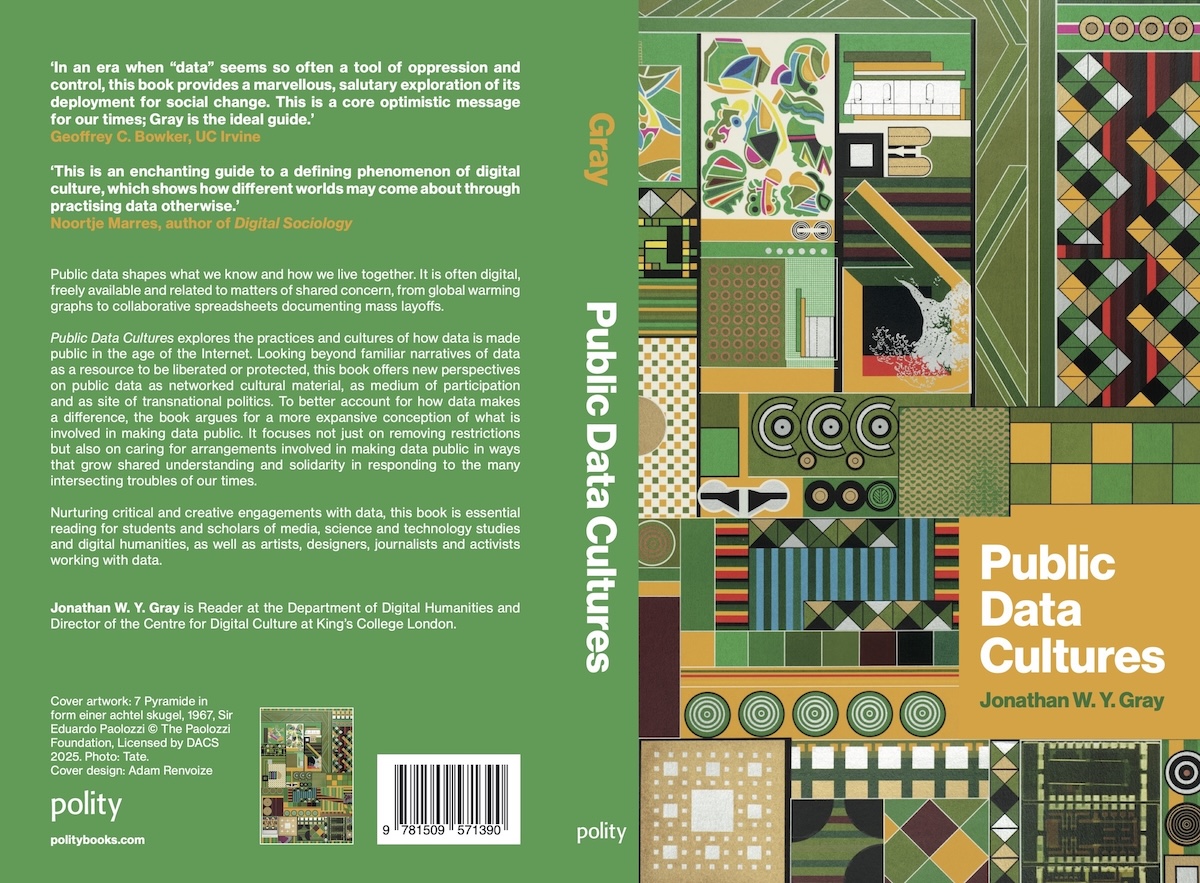

The acknowledgements section in the book is long. Many friends, colleagues and loved ones helped me and the book along in many ways. I wish my dad had made it to see the cover which he’d know from galleries we went to as kids when visiting family in Scotland.

The book is meant to be more than academic, and is dedicated to the people who made me – Sin Chin, Yun Yin, Joyce, Nelson, Carol, Bill and Rebecca - all committed to social reproduction and remaking the world through nursing, teaching, mental health and community work.

In a nutshell, the book aims to nurture critical and creative engagements with public data. It explores practices and cultures of how data is made public in the age of the Internet.

The first part of the book reconsiders data as cultural material, medium of participation and site of transnational politics.

The second part of the book explores different ways of critically engaging data. This includes making data in response to missing data on police killings, corporate tax avoidance and coal power plants.

It concludes with a review of critical data practices described as decolonial, feminist, Indigenous, more-than-human, queer, speculative, thick, warm, weird and more.

I’ll be doing some book talks in coming months and in 2026. If you’d be interested in hosting something let me know. If you’d like to write something about the book, use it into a class or otherwise bring it into the world, you can write to me. 💌

If you read it, I hope you find something that resonates.

reviews

“In an era when ‘data’ seems so often a tool of oppression and control, this book provides a marvellous, salutary exploration of its deployment for social change. This is a core optimistic message for our times; Gray is the ideal guide.” - Geoffrey C. Bowker, UC Irvine

“This is an enchanting guide to a defining phenomenon of digital culture, which shows how different worlds may come about through practising data otherwise.” - Noortje Marres, author of Digital Sociology

blurb

Public data shapes what we know and how we live together. It is often digital, freely available and related to matters of shared concern, from global warming graphs to collaborative spreadsheets documenting mass layoffs. It circulates via maps and apps which enable us to discover, report and rate what is around us.

Public Data Cultures explores the practices and cultures of how data is made public in the age of the Internet. Looking beyond familiar narratives of data as a resource to be liberated or protected, this book offers new perspectives on public data as networked cultural material, as medium of participation and as site of transnational politics. To better account for how data makes a difference, the book argues for a more expansive conception of what is involved in making data public. In doing so, it focuses not just on removing restrictions but also on caring for arrangements involved in making data public in ways that grow shared understanding and solidarity in responding to the many intersecting troubles of our times.

Nurturing critical and creative engagements with data, this book is essential reading for students and scholars of media, communications, Internet studies, science and technology studies and digital humanities, as well as artists, designers, engineers, reporters, public sector workers, community organisers and activists working with data.

contents

Introduction

I. RECONSIDERING DATA

1. Data as cultural material

2. Data as medium of participation

3. Data as transnational coordination

II. CRITICALLY ENGAGING DATA

4. Missing data and making data

5. Critical data practices

Conclusion

Updated on 24th October, as there was more to say and the 23rd was a busy day!