New piece: “Is “another internet possible”? Inside Labour’s digital infrastructure plans” in Open Democracy

December 06, 2019

The following piece is cross-posted from OpenDemocracy, where it was published on 4th December 2019.

The Labour Party’s recently launched manifesto and associated proposals contain the seeds of an egalitarian, progressive vision of the role that digital, data and knowledge infrastructures might play in contemporary life. While their proposals on broadband, tax, data, patents, platforms, AI and digital rights have largely been reported and evaluated separately, together they serve as a reminder that “another internet is possible”.

The past few years have seen a series of critiques of the exploitative capacities of digital technologies, such as “platform capitalism”, “surveillance capitalism” and “data colonialism”. Large technology companies such as the “big four” (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple) proliferate devices and interfaces which gather data for advertising and targeting, facilitated by aggressive tax avoidance in countries where they operate.

Online platforms such as Uber and Deliveroo promote exploitative and precarious “gig” work. The algorithms, tracking ecosystems and personalisation mechanisms of search and social media companies contribute to the commodification of public life, the polarisation of political debate, as well as new forms of discrimination and inequality. As new media scholar Richard Rogers frames the recent turn in public discourse, “instead of emancipatory, the web became authoritarian, with Shirky’s web supplanted by Morozov’s”.

In response to these developments, Labour have committed to taxing multinational corporations (“including tech giants”) in proportion to their economic activities by closing loopholes and changing rules which currently enable avoidance at a massive scale ($100 billion in avoidance for just six firms over the past decade, according to one recent report). The manifesto also proposes a new “Charter of Digital Rights” which would challenge algorithmic injustice, surveillance and support user rights for access and ownership to their data.

In addition to this agenda of redistribution, regulation and rights, Labour’s manifesto also contains proposals around alternative arrangements for the ownership, governance and control of digital and data infrastructures. Most prominent are the “free full-fibre broadband for all” proposals through the creation of a new “British Broadband” public service building on the successes of publicly owned networks around the world.

As internet studies and science and technology studies researchers have argued for many decades, digital infrastructures are not just neutral vehicles, but embody different kinds of values, politics and relations. Prioritising public access over private profits, publicly owned broadband networks challenge the long-standing assumption that “corporations necessarily provide connectivity”. British Broadband could commit to lowering environmental impacts by repurposing existing fibre, rather than laying new cables.

Taken together, Labour’s proposals for British Broadband and the Charter of Digital Rights suggest the possibility of changing not only the means but also the meaning of connectivity. With a shift from broadband as commercial service to broadband as a public commons comes the promise of reconfiguring relations between digital infrastructures and their users – for example, figuring the latter as networked citizens with expertise to offer rather than surveilled consumers from whom value can be extracted through transactional data.

In contrast to recent leaked negotiation documents which show US interest in obtaining access to NHS data, extending drug patents and raising drug prices, Labour propose to consolidate public investment and democratic control over digital infrastructures for medical research and data. In their Medicines for Many report, the party proposes to establish a “publicly owned pharmaceutical and manufacturing body” in order to “deliver the medicines we need at prices we can afford” by developing and supporting “generic” medicines. On top of supplying cheaper medicines for the UK, the initiative would address historical injustices and “incorporate principles of collaboration and solidarity” by ensuring open access to publicly funded research, promoting “fairer international patent regimes” and guaranteeing that “medicines developed with the support of UK taxpayer money are accessible to people in the Global South”.

Labour’s digital proposals do not represent a naive return to earlier visions of the social web which emphasised participation and collaboration (often through private infrastructures for the commodification of attention and user data). Nor do they accept that we are powerless against the extractive and surveillant capacities of digital technology. Nor do they endorse the default positions established by major digital policy initiatives in the 1990s, such that “National Information Infrastructure” should be “built, owned and operated by the private sector” and that public institutions should avoid “entering markets in which private-sector firms are active”. Rather they offer a bold future-oriented vision of digital infrastructures and the role they might play in collective life.

Instead of taking these plans as a finished blueprint, perhaps they may be taken as an invitation to think beyond the “regulatory state” and market-oriented approaches towards exploring other forms of institutional imagination and arrangements around the ownership, governance and capacities of digital and data infrastructures – such as creating national data funds and collective data banks; intervening around algorithmic systems; transforming platform work; socialising “feedback infrastructures”; and exploring data infrastructures as sites of participation around both local and transnational issues.

Digital infrastructures currently oriented towards extraction, exploitation and profit might instead facilitate solutions to pressing societal issues, such as inequality, housing, land reform, climate change and public health. In complement to initiatives promoting the use of public data for progress around the United Nations “Sustainable Development Goals” (#data4sdgs) which often focus on policy-making and public institutions, data may serve as a site of broader public participation around a Green New Deal (#data4gnd?) to ensure that climate plans also serve to address, rather than exacerbate, regional and historical inequalities. Labour’s proposals are a welcome step towards radically rethinking the role that digital infrastructures might play in addressing urgent public problems.

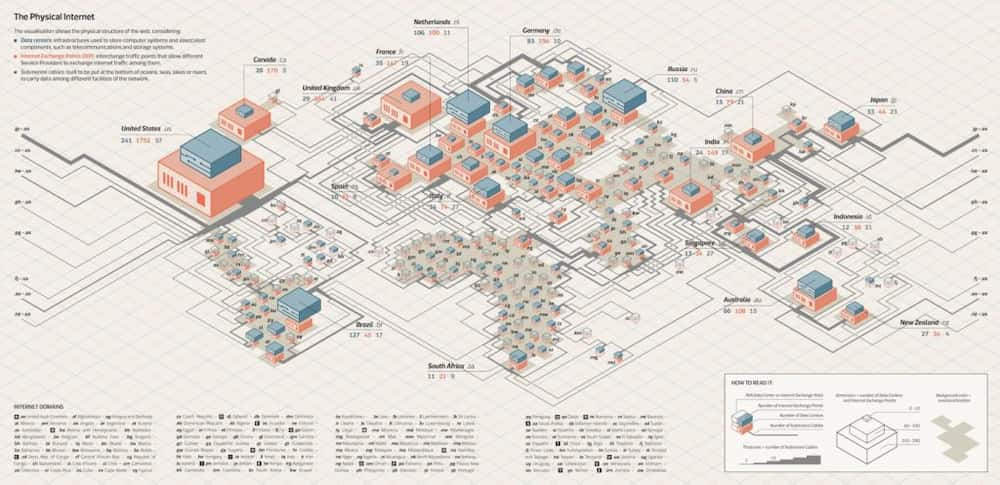

“The Physical Internet” visualisation from DensityDesign Lab can be accessed here.