Making Climate Negotiations Public

December 09, 2015

This piece was originally published in Open Democracy on 9th December 2015. It was co-authored with Tommaso Venturini and Rufus Pollock.

World leaders are currently gathered in Paris in order to coordinate action around climate change. It is no exaggeration to say that the future of our planet will depend on what they decide.

But how much will the rest of us learn about the circumstances of these decisions to determine our collective fate? Will the deliberations be made public – so that civil society groups can hold decision-makers democratically accountable for their commitments? Or will what happens in Paris effectively stay in Paris?

In principle the entire world is represented by the tens of thousands of participants assembled in the vast conference complex in Le Bourget which the organisers characterise as “a temporary city which never sleeps”. As well as dozens of national offices and parallel negotiation rooms, over 3,000 journalists and hundreds of civil society groups are present – including environmental NGOs, youth groups, indigenous groups, trade unions, industry associations and many others.

As the negotiations roll on, the eyes and attention of the world are directed at one vitally important element. Not on a single leader, country or organisation – but rather on a piece of text. The draft treaty text that is currently being finalised will serve as the centrepiece for what comes out of the Paris negotiations, and for what comes after.

Many of the world’s manifold and competing interests are supposed to be taken into account in this piece of text – which will in effect serve as a germinal blueprint for our collective agenda to recompose the world in light of climate change.

If the current climate negotiations in Paris can be seen as a dramatic cliffhanger of a television series, then the full cast of characters and backstories implicated in this unfolding drama can be found in an accompanying set of texts called the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Making these sets of texts accessible is essential to broadening meaningful democratic engagement before, during and after global climate negotiations – both in Paris and beyond. Particularly as the casts of actors and issues tend to be formidably large – many with unwieldy names and complicated backstories, as anyone who has tried to unpick the acronyms and follow the subtopics will know.

In order to advance this agenda of making climate negotiations public, the médialab at Sciences Po in Paris has been collaborating with the global civil society organisation Open Knowledge to create a set of tools and resources to put the Paris talks into context.

To start with, we want to tell the story of the treaty text itself. How has this text evolved? Who was responsible for changing different bits of the text? Which bits were the most controversial and why? What is at stake for whom in different parts?

The polished veneer of the final text may betray little about the highly political and contested process of its making. The text is currently published as a PDF – a file format which now has a reputation amongst civic hackers and open data advocates for being notoriously difficult to parse and analyse, as well as being hard to index, search for and link to.

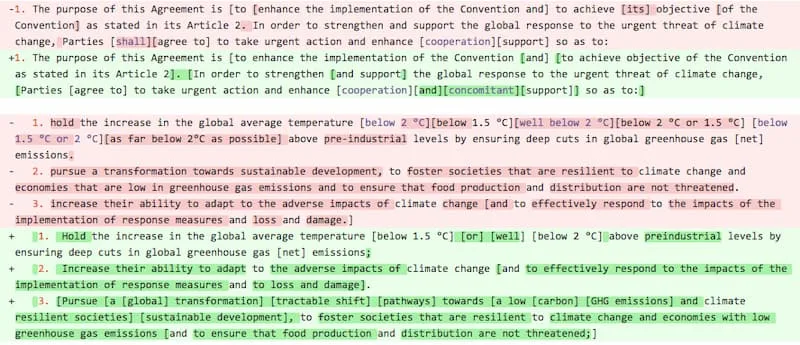

So our first (rather painstakingly and thankless) task was to convert it into a text form which is more suitable for analysis – which we did here. This lets us see a bit more about the politics of text’s composition, including comparing different versions to see how it has evolved over time and which parts were most edited and contested. For example, comparing the initial pre-negotiation text from 23rd October 2015 with the version from Friday 4th December shows many different views about whether the limit for global average temperature increase should be 1.5º or 2º celsius.

In order to begin to unpick and unpack the text, there are a bewildering number of acronyms, subgroups, discussion papers, chairs to make sense of. To understand what these mean and to put them into context we could turn to the previous negotiation transcripts provided by the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

In an ideal world – this might mean we could easily explore how the positions of different actors have evolved over time or see previous debates about a given topic. However, there are currently no standard ways of formatting and describing the texts, which means that this is currently not possible. This hugely limits the accessibility of ongoing climate negotiations, such that only a comparatively small minority of experts are able to meaningfully follow the plot.

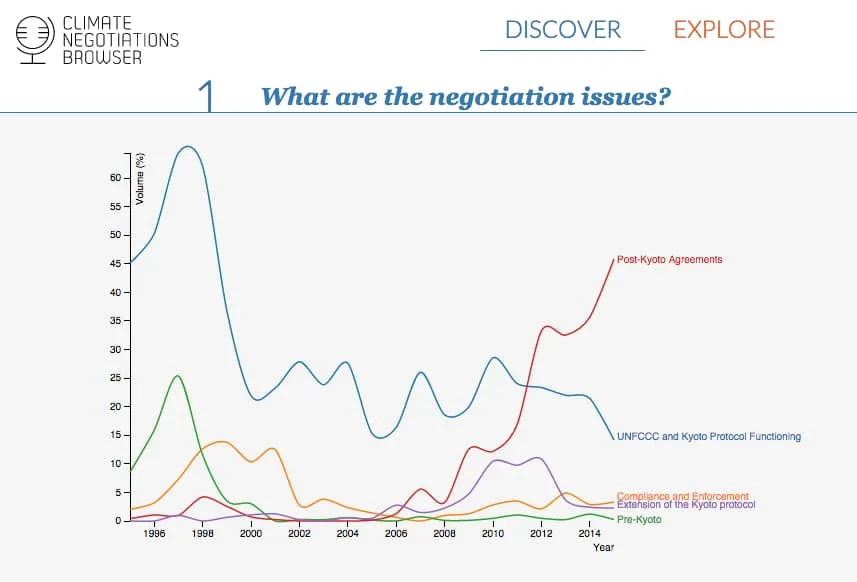

The médialab at Sciences Po have started work to extract and classify the texts of past negotiations leading. This has culminated in the release of the climate negotiations browser ahead of the Paris talks. From this we start to can put the current talks into context – including looking at the rise and fall of different topics (such as climate financing and assessing vulnerability) and the respective positions and priorities of different countries in the discussions.

However, much more needs to be done to improve the public record of what is being negotiated in our names. The UN has called for a “Data Revolution” in sustainable development calling data the “lifeblood of decision-making and the raw material for accountability”. But it is not only snapshots of public statistical databases that need to be improved and invested in, but the public texts give us a glimpse of politics in the making. If they are well organised and structured, they could provide civil society with a powerful analytical resource to inform their activities.

These texts represent a thin but vital connection between the words of world leaders and the ears of everyone else who is able to tune in. Without them, informed democratic engagement around the negotiations is simply not possible.