Who read what? Mapping influence in intellectual history

February 20, 2011

In my research I often wonder about whom and what the people I’m reading read. Did Wittgenstein read Nietzsche? Did Nietzsche read Hegel? Did Hegel read Shakespeare? Did Shakespeare read Chaucer? Did Chaucer read Sophocles?

Knowing which texts a given writer was aware of (and which they probably weren’t aware of) can help us to understand them and their works better. For example, I may notice a certain idea or metaphor in a text, which reminds me of something someone else has written a hundred years before. Is it possible they knew about the earlier text? Is there evidence they were acquainted with it (directly or indirectly)? Similarly I may notice something in a text which reminds me of something which somebody said much later. Is there any evidence of influence? Is a comparison anachronistic? Did the author of the passage I’m reading know about another influential essay or tract on the same topic pubished a couple of decades earlier? Knowing what someone read gives us a sense of where they are coming from, gives us a sense of the contours of what Gadamer would call their Horizont, their ‘horizon’.

Large scale collaborative research in the humanities does not always make sense. Many academics may feel that they scarcely have time apart from teaching and admin to do their own research (writing books, etc), let alone big research projects with people with whom they do not know, and whose work may be only approximately or tangentially related to their own. Certainly people sitting on research funding councils and so on should be careful not to unreflectingly promote collaborative research models in arts and humanities disciplines from other research areas, for example in the sciences, where large scale collaboration is ubiquitous or necessary. That said, I do think that a lot of meta level activities – such as creating and maintaining comprehensive bibliographies – are more suited to being undertaken by large communities of scholars working in collaboration, rather than by lone experts in isolation. Mapping influence in intellectual history is arguably an endeavour where it is desirable to have as much input as possible from as many pairs of eyes as possible.

How might we get started? How can we enable collaboration between scholars to start systematically mapping influence between different writers? To start with we have an increasing amount of freely reusable information about authors and works, e.g. open data from the British Library, the Library of Congress and elsewhere. These can often tell us who wrote what, and the dates of publication of work, and the birth/death dates of authors. Building on this, we could create a basic tool which enable scholars to create new relations between these basic elements, and to explore those relations.

Ideally one would want to have a minimal number of these relations, and for each of these to be as well formed and unambiguous as possible, and each able to be substantiated with some kind of textual reference. E.g. rather than having ‘author X was influenced by author Y’ or ‘author X was aware of author Y’ one would want to break these down into very simple, concrete things like:

- Work A quotes from Work B

- Work A cites Work B

- Work A alludes to author X

- etc

One could even imagine using other sources (library lending data, lecture lists, reading lists, catalogues, letters, notes and other sources) to try to systematically establish things like:

- Author X corresponded with author Y

- Author X met author Y

- Author X was taught by author Y

- Author X attended lectures on author Y

- Author X possessed a copy of work A

- Author X borrowed book A from a library

- etc

This kind of tool would have to be used with a good measure of caution, to ensure one does not:

- Shoehorn one’s interpretation of influence into a certain pre-defined (and to a certain degree, arbitrary) scheme. Hence the first cluster of relations may be more solid start than the second, which are a bit more tentative.

- Take this kind of data as anything other than a very rough guide, an initial basic reference pointing scholars to further sources and citations, which should be interpreted carefully. As I blogged about recently , I don’t think guidance from digital tools will replace immersion in a given domain any time soon!

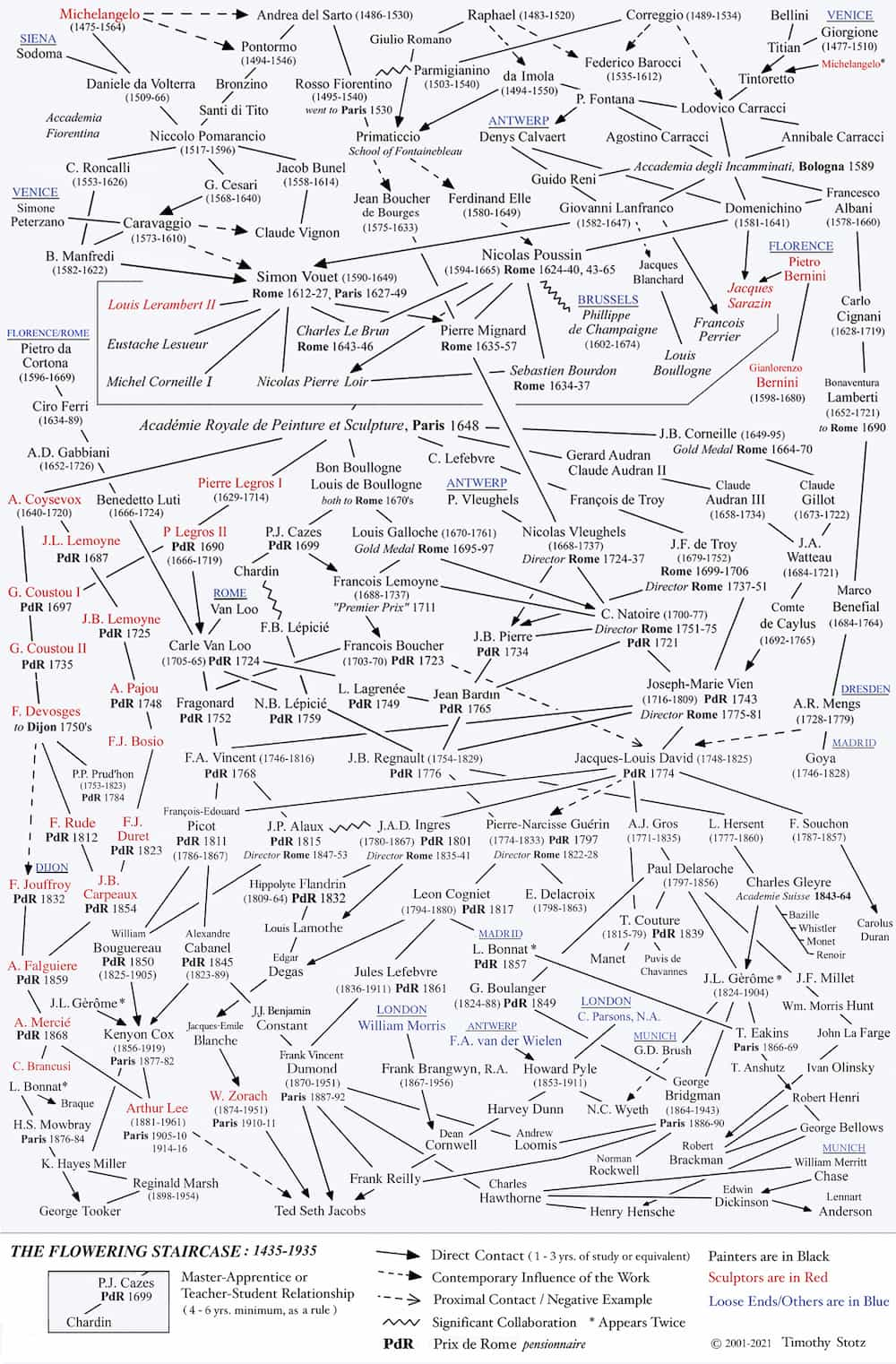

The image above is from Timothy Stotz, and shows teacher-student relationships between artists, 1435-1935